Pediatric Pearls #1. The Newborn Metabolic Screen: What’s Pearl S. Buck got to do with it?

November 12, 2024

Welcome back Tuesday Pediatric Pearls

Starting today and for the winter months, I plan to bring back Tuesday Pediatric Pearls for paid subscribers. This first one will go out to everyone (free and paid subscribers) so folks can get an idea of what these posts are like. Most will be a resurrection of the first Pediatric Pearl post series – with tweaks and updates and polishing. Enjoy!

In this post, let’s take a look at the newborn metabolic screen, how it’s done and what it tests for. The answer to the question asked in the title about Pearl S. Buck will come towards the end.

State by state (and country by country!)

In the United States, each state has its own newborn metabolic screening program and sets its own rules. There is no national standard. I live and work in a hospital in Massachusetts, where we are required by the MA Department of Public Health to obtain a newborn metabolic screen from each newborn that we care for prior to discharge from the Mother Baby Unit.

When is it done?

Ideally the blood sample is obtained when the infant is 24-48 hours of life, but any time after 24 hours until discharge from the hospital is fine for a healthy infant. It is important to give the infant at least 24 hours of eating to generate abnormal metabolites that can be picked up on the screen. The timing of the newborn screen(s) is different for infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Often many more screens are obtained.

How is it done?

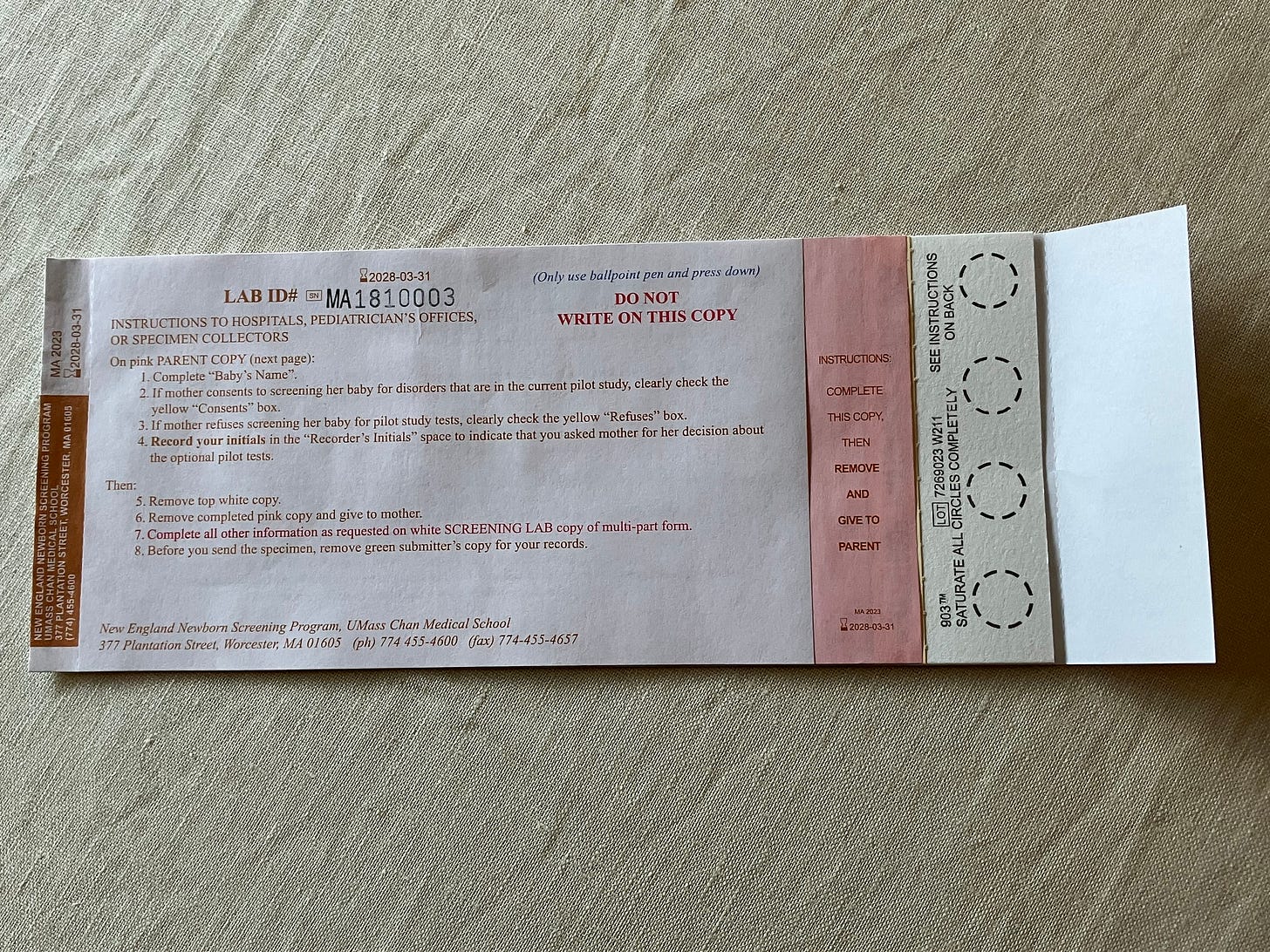

The state provides the hospital with newborn screening cards. Information is collected from the infants’ parents including address and phone numbers.

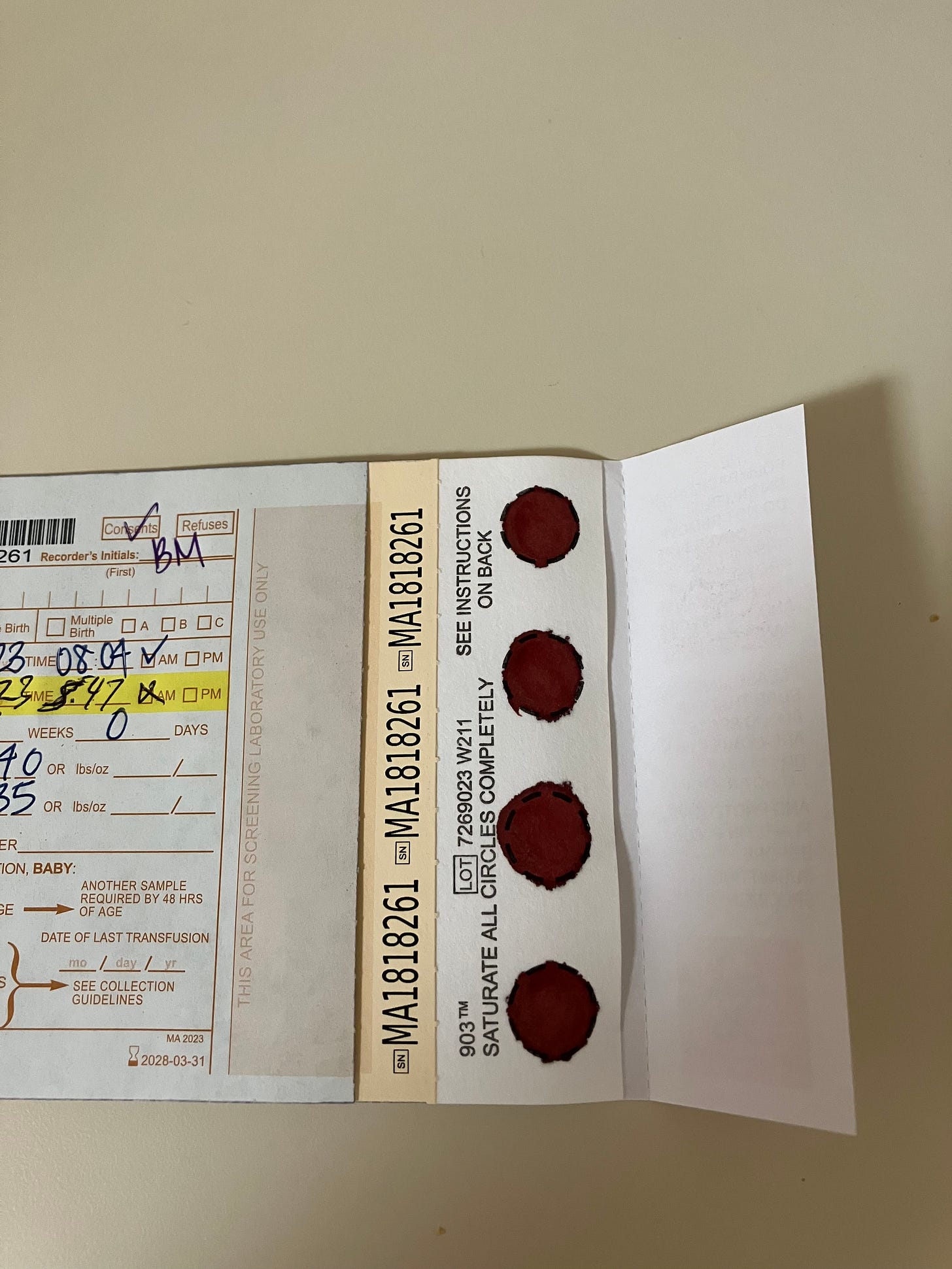

The infant’s heel is pricked and four circles on the bottom of the card are fully saturated with blood.

Once the card dries, it is transported to the hospital laboratory where it is logged into our EPIC system and then sent, on a daily basis, to the state’s screening site. Our job is to be sure the blood sample is obtained; the infant’s provider’s job is to be sure the results are checked. Results take about 7-10 days to come back, but if something abnormal is detected the state lab will call immediately.

What is screened?

Who decides which disorders are included in the newborn screen?

In Massachusetts, the Commissioner of Public Health decides which disorders are tested for with input from an Advisory Board made up of doctors, nurses, scientists, ethicists and parents. For a disorder to be included the following must be true:

The disorder is treatable.

There is a good test.

Early medical intervention would benefit the infant.

The newborn metabolic screening program in Massachusetts started in 1962 with screening for one condition. Massachusetts now tests for 32 mandatory conditions. There is also an option to test for 8 additional conditions for which pilot studies are underway. The 32+8 conditions are listed at the end of the article.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. Nurses in my hospital call it the PKU test. Why?

A. This is probably because the first newborn screen was for phenylketonuria (PKU).

Other’s might call it the Guthrie test! The history behind what we now know as the Newborn Metabolic Screen is fascinating. It started with the discovery that a drop of ferric chloride would turn a select group of children’s urine a distinct color. The substance in the urine was phenylalamine. Fast forward to 1962, when Robert Guthrie invented a diagnostic tool to test infants for phenylketonuria a few days after birth. The “Guthrie card” was filter paper on which an infant’s blood could be collected. Using a blood spot (a small piece of the blood in one of the circles), a bacterial inhibition assay could be performed looking for elevated levels of phenylalanine. The next advancement was using mass tandem spectrometry for the testing.. This has allowed many more conditions to be screened. As noted, Massachusetts now tests for 32 conditions using the four saturated circles.

Q. Which newborn screen is required by all US states and territories?

A. All 50 U.S. states and territories require that newborns get screened for PKU.

Q. What happens if a mother wishes to leave early, say on day one of life when infant is less than 24 hours of life?

The infant needs enough time to generate metabolites that are being tested. The test is not considered valid unless done after 24 hours of life. We try to get mother and baby to stay until infant is at least 24 hours old, but if she wishes to leave then we obtain a NMS prior to discharge and carefully document the age of the infant when it was obtained. We also contact the PCP office so they are aware and will retest.

Q. Can parents refuse?

In MA, parents can refuse. In that case, at our hospital, a form is signed by both parents documenting that this is their wish and the hospital lawyers are contacted so they are aware. We may call the Patient Advocate and we also carefully document discussions held with the parents.

Q. Is extra blood needed for the pilot studies?

A. No, no extra blood is required.

Q. What are some of the challenges of running such a program?

A. It is crucial that a family can be reached if the state lab identifies a problem in one of the screens. Demographic and contact information is collected along with the blood sample.

Sometimes the blood sample obtained is insufficient. The issue is usually that each circle was not fully saturated. In this case the family would be notified and another sample would be collected from the infant asap.

What’s Pearl S. Buck got to do with it?

We need to dive into the history books to learn about the connection between Pearl S. Buck and newborn metabolic screens.

“In 1921, Pearl S. Buck gave birth to a daughter, Carol, who became severely retarded and was eventually institutionalized at the Vineland Training School in New Jersey. To help pay for her daughter's care, Buck wrote The Good Earth in 1931, and then other novels and biographies about her life in China, for which she was awarded the Nobel and Pulitzer Prizes, and honored around the world. Years later, she published The Child Who Never Grew, a short piece about her daughter's retardation that also revealed her desperate search for answers and good clinical care. Asbjørn Følling distinguished phenylketonuria (PKU) from other forms of childhood retardation in the mid-1930s, and new assays and biochemical findings eventually led to ways to circumvent the devastating effects of PKU. But for Carol Buck, these advances came too late. It was not until the 1960s that physicians confirmed that her severe retardation was caused by PKU.” J Hist Neurosci. 2004 Mar;13(1):44-57. doi: 10.1080/09647040490885484.

This is what is screened for by the newborn metabolic screen in the state of Massachusetts in the United States. What is screened for where you live?

The 32 Mandatory Conditions screened for by the MA Newborn Metabolic Screen are:

Argininemia (ARG)

Argininosuccinic acidemia (ASA)

β-Ketothiolase deficiency (BKT)

Biotinidase deficiency (BIOT)

Carbamoylphosphate synthetase deficiency (CPS)

Carnitine: acylcarnitine translocase deficiency (CACT)

Carnitine uptake defect (CUD)

Citrullinemia (CIT)

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH)

Congenital toxoplasmosis (TOXO)

Cystic fibrosis (CF)

Galactosemia (GALT)

Glutaric acidemia type I (GAI)

Homocystinuria (HCY)

3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaric aciduria (HMG)

Isovaleric acidemia (IVA)

Long-chain L-3-OH acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHAD)

Maple syrup disease (MSUD)

Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTC)

Phenylketonuria (PKU)

Sickle cell anemia (Hb SS)

Hb S/C disease (Hb SC)

Hb S/β-thalassemia (Hb S/βTh)

Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCAD)

Methylmalonic acidemia: mutase deficiency (MUT)

Methylmalonic acidemia: cobalamin A, B (Cbl A,B)

Methylmalonic acidemia: cobalamin C,D (Cbl C,D)

Propionic acidemia (PROP)

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID)

Tyrosinemia type I (TYR I)

Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (VLCAD)

A total of 8 pilot studies are underway. The first 4 pilot studies tested for are:

Dienoyl-CoA reductase deficiency (DE RED)

Hyperornithinemia, Hyperammoninemia, Homocitrullinemia Syndrome (HHH)

Malonic acidemia (MAL)

Medium/short-chain L-3-OH acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (M/SCHAD0

In January, 2018, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health implemented voluntary pilot screening for 4 more conditions:

Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I (MPS-I)

Pompe Disease

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)

X-linked Adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD)