Terminology

Here are a few terms to review before diving into the important topic of hyperbilirubinemia.

Bilirubin – a yellow-orange pigment that occurs from the breakdown of heme, mostly from red blood cells

Hyperbilirubinemia – a high amount of bilirubin in the blood

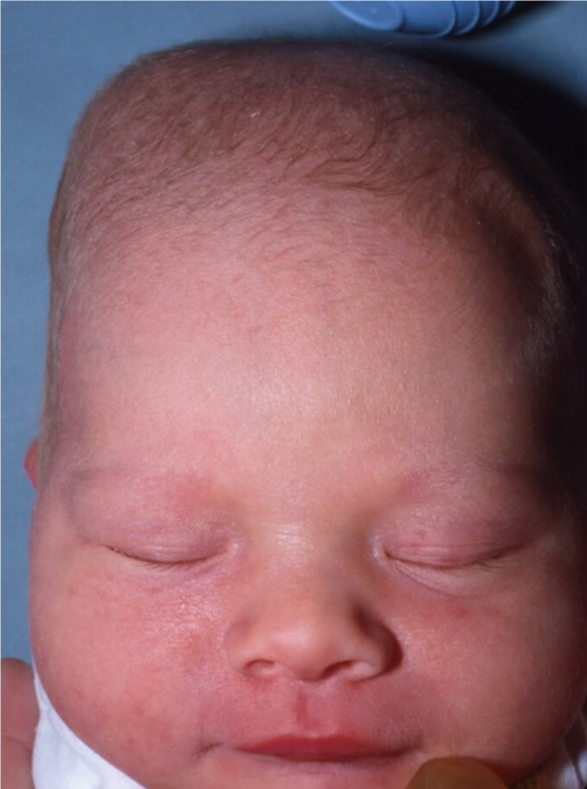

Jaundice - a medical condition in which the skin, mucous membranes and whites of the eyes turn yellow due to a high level of bilirubin

Scleral icterus – yellow color in the whites of the eyes

Cephalocaudal progression – yellow color of the body going from the head to the toes

As a hospitalist on the MotherBaby Unit, I deal with hyperbilirubinemia all the time. I am extremely careful about this issue and obtain frequent bilirubin checks on babies I am caring for. Indeed, per policy on our unit, every baby must have at least one total serum bilirubin checked prior to heading for home from the maternity unit. Then the infant is given a Primary Care Provider (PCP) check for 3-5 days OF LIFE so this can be further followed. This appointment often is for the day after leaving the hospital.

For test takers, as the IBCLC-exam is an entry level exam, I don’t know the extent that one needs to understand this topic. But, given that hyperbilirubinemia is so common in infants, I think a basic understanding is expected and you should expect several questions on this.

Buckle your seat belts - here we go.

Where does bilirubin come from?

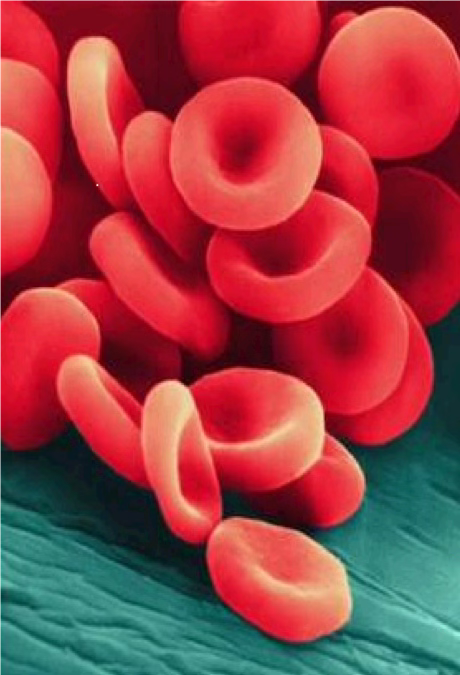

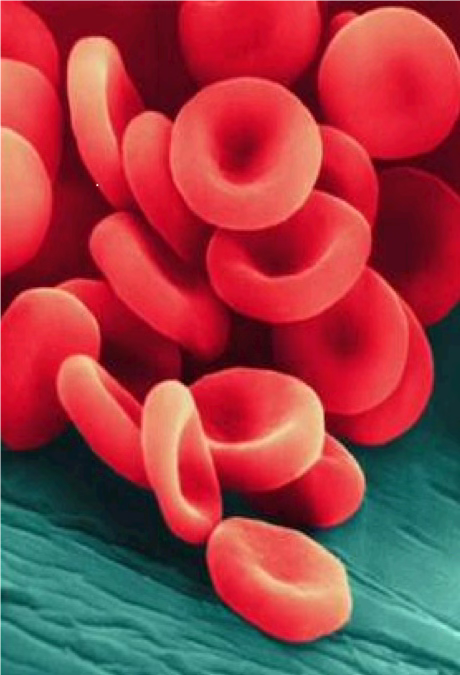

Most bilirubin (80%) comes from the breakdown of red blood cells.

Red blood cells contain hemoglobin that is broken down to heme and globin.

Heme is broken down to biliverdin, which is then broken down to bilirubin.

The body tries to get rid of the bilirubin. To do this, the bilirubin in the blood stream has to get to the liver.

Bilirubin metabolism, a review

Red blood cells break down into hemoglobin which breaks down into heme and globin.

Heme breaks down to biliverdin, which becomes bilirubin.

This bilirubin, before getting to the liver, is in an unconjugated form. Via a blood test, this is measured in the laboratory as “indirect” bilirubin.

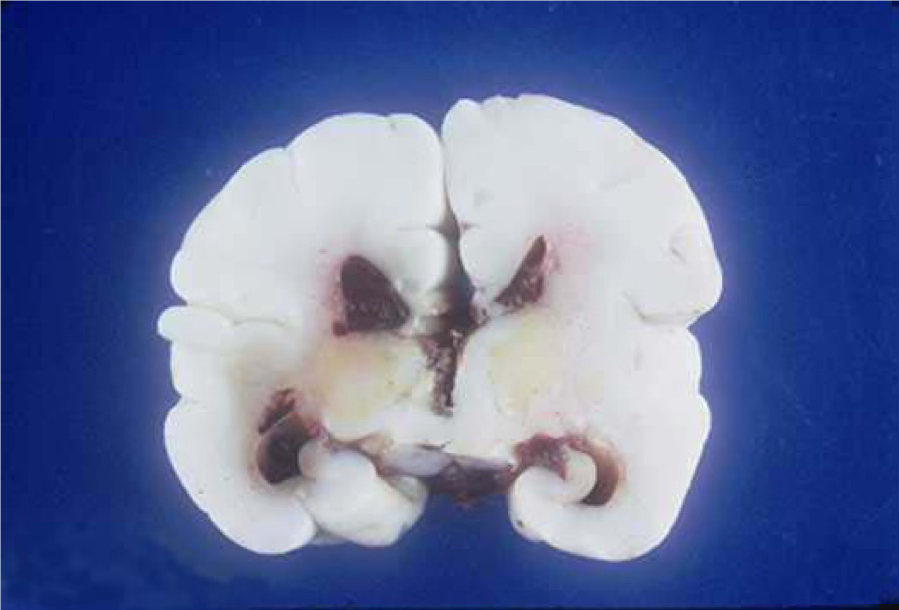

Bilirubin in the unconjugated form is fat soluble. This is a problem because unconjugated bilirubin can cross the blood brain barrier and deposit into brain tissue. Too much bilirubin in the brain can cause a serious condition called kernicterus.

In the blood, unconjugated bilirubin is transported to the liver bound to the protein, albumin. Think of albumin as an UBER – it picks up unconjugated bilirubin in the blood stream, puts it in a seat belt, holds it tightly, and delivers it to the liver. Any unconjugated bilirubin that is free, or not bound to albumin, can cross the blood brain barrier.

A high level of bilirubin in the blood stream can overwhelm the amount of albumin that is available, float around in a free form, and become quite dangerous. Again, too much bilirubin getting into the brain it can cause kernicterus. Test takers should know that term. You can see the yellow staining in the slice of brain below. This indicates that unconjugated bilirubin has crossed the blood brain barrier and is deposited in brain tissue.

Clinically this would initially present in the infant: sleepiness, poor feeder, high pitched cry, arching of the neck, increased tone. Later on: athetoid cerebral palsy, hearing loss, motor spasticity.

Back to that UBER. The albumin-bound unconjugated bilirubin has now arrived at the liver where three things happen.

The bilirubin is taken up into the liver.

Within the liver cells (which are called hepatocytes), the bilirubin is conjugated.

For bilirubin to be conjugated, this step requires an enzyme called uridine diphosphate glucosolytransferase (UDGPT). Via a blood test, conjugated bilirubin is measured as “direct” bilirubin. Conjugated bilirubin is water soluble. It cannot cross blood brain barrier.

Conjugated bilirubin in the liver cells is excreted into the biliary tract, and, then into the small intestine.

In the gut, the bilirubin travels down to the ileum and then the colon, waiting to be passed out of the body. Bacteria in the gut can change it to stercobilin (which is what makes the feces brown) and urobilinogen which ends up back in the body and gets peed out (making the urine yellow).

But here is the kicker.

If it sits there long enough, conjugated bilirubin can be converted by intestinal bacteria back to unconjugated bilirubin. If the unconjugated bilirubin sits and sits and sits in the gut, it gets sucked back into the body to the liver via the enterohepatic circulation. And here we go again

That is why we love stool! Stooling helps get the bilirubin pigment out. (Fact: meconium is the dark color it is due to bilirubin pigment.)

So now it should be clear why bilirubin in the blood stream can be in two forms:

Unconjugated (indirect) and

Conjugated (direct)

In the hospital I can order a total serum bilirubin (TsB). This is made up of the indirect (unconjugated) + direct (conjugated) forms of bilirubin. I can also order a direct bilirubin alone.

Example: if the TsB (total serum bilirubin) is 14, and the direct bilirubin is .5, then the indirect bilirubin is 13.5. I hope that makes sense.

Physiologic and non-physiology jaundice

Next, be aware that there are two kinds of elevated bilirubin in the infant: physiologic and non-physiologic.

Physiologic jaundice

Physiologic jaundice is jaundice we expect to happen. You could say, this is “normal”.

Most infants get a little yellow, right? It occurs normally in 60% of term newborns and 80% of preterm infants

For term infants the average peak bilirubin level is 5-6 mg/dl. (Your bilirubin level and my bilirubin level today are probably less than 1 mg/dl.)

The progression of jaundice (or the yellow color) goes from the head to the toes. This is called cephalocaudal progression.

The bilirubin pigment can be seen in the skin, mucous membranes and whites of the eyes.

Newborn infants have numerous factors that are the reason for physiologic jaundice:

High blood volume and increase hematocrit concentration (normal infant hct is 45-65)

Shorter life span of fetal red blood cells

Activity of neonatal UDGPT is lower than adults

Absence of the clostridial gut flora needed for the conversion of bilirubin to stercobilin results in higher concentration of bilirubin in the intestinal tract

The mucosal enzyme, beta glucuronidase is more active in the infant small intestine. In the setting of a more permeable infant gut wall, this high concentration of unconjugated bilirubin results in increased enterohepatic circulation.

In infants, a little bit of an increase in bilirubin is a normal thing, as the bilirubin pigment acts as an anti-oxidant in the cells, soaking up free-radicals that could damage the cell.

HOWEVER, a big increase in the bilirubin level can be a dangerous thing.

Non-physiologic jaundice

Non-physiologic jaundice is a different story. It can be due to:

Over production of bilirubin or

A decreased clearance of bilirubin

Key point: jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is NEVER normal and needs an immediate investigation.

Overproduction causes include:

Hemolysis – when the red blood cells break up. A common cause of this is ABO incompatibility. Mother and baby blood groups differ causing hemolytic disease which means the excessive breaking up of red blood cells. Another cause is Rh incompatibility. Another cause is G6PD deficiency.

Excessive bruising

Cephalohematoma. This is a collection of blood typically seen on one or both sides of the head in the parietal area. It is differentiated from a caput succedaneum in that a cephalohematoma does not cross suture lines.

Another common cause of decreased clearance is a baby who is not stooling. This can be caused by poor feeding. The next post will compare poor breastfeeding jaundice and breast milk jaundice.

References

Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession, 7th edition. Mosby, an imprint of Elsevier Inc. 2011

Core Curriculum for Interdisciplinary Lactation Care. Edited by Suzanne Hetzel Campbell, Judith Lauwers, Rebecca Mannel, and Becky Spencer. LEAARC (Lactation Education Accreditation and Approval Review Committee). Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2019

Wambach K, Spence B. Breastfeeding and Human Lactation, 6th edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2021

Tema #50. Infantil Parte 3. Viendo Amarillo: Comprendiendo la Hiperbilirrubinemia

Aquí hay algunos términos que debemos revisar antes de sumergirnos en el importante tema de la hiperbilirrubinemia.

Bilirrubina – un compuesto amarillo-anaranjado que se produce por la descomposición del hemo

Hiperbilirrubinemia – cantidad elevada de bilirrubina en la sangre

Ictericia – condición médica en la que la piel, las membranas mucosas y el blanco de los ojos se vuelven amarillos debido a un alto nivel de bilirrubina

Ictericia escleral – color amarillo en el blanco de los ojos

Progresión cefalocaudal - color amarillo del cuerpo que progresa desde la cabeza hasta los dedos de los pies

Como hospitalista, me ocupo de la hiperbilirrubinemia todo el tiempo. Soy extremadamente cuidadoso con este tema y realizo controles frecuentes de bilirrubina en los bebés que cuido. De hecho, según la política de nuestra unidad, a cada bebé se le debe controlar al menos una bilirrubina sérica total antes de regresar a casa desde la unidad de maternidad. Luego, el bebé recibe un control del proveedor de atención primaria (PCP) durante 3 a 5 días DE VIDA para que se pueda realizar un seguimiento más detallado. Esta cita suele ser para el día siguiente.

Para los examinados, dado que el examen IBCLC es un examen de nivel inicial, no sé hasta qué punto es necesario comprender este tema. Pero, dado que la hiperbilirrubinemia es tan común en los bebés, creo que se espera una comprensión básica y se deben esperar varias preguntas al respecto.

Metabolismo de la bilirrubina

¿De dónde procede la bilirrubina?

La mayor parte de la bilirrubina (80%) procede de la descomposición de los glóbulos rojos.

Los glóbulos rojos contienen hemoglobina que se descompone en hemo y globina.

El hemo se descompone en biliverdina, que a su vez se descompone en bilirrubina.

El cuerpo intenta deshacerse de la bilirrubina. Para ello, la bilirrubina del torrente sanguíneo debe llegar al hígado.

Metabolismo de la bilirrubina, una revisión

Los glóbulos rojos se descomponen en hemoglobina, que a su vez se descompone en hemo y globina.

El hemo se descompone en biliverdina, que se convierte en bilirrubina.

Esta bilirrubina (antes de llegar al hígado) es no conjugada. Mediante un análisis de sangre, se mide en el laboratorio como bilirrubina "indirecta".

La bilirrubina en forma no conjugada es soluble en grasa. Esto es un problema porque la bilirrubina no conjugada puede atravesar la barrera hematoencefálica. Un exceso de bilirrubina en el cerebro puede provocar una enfermedad grave llamada kernícterus.

En la sangre, la bilirrubina no conjugada es transportada al hígado unida a la proteína albúmina. Piensa en la albúmina como un UBER: recoge la bilirrubina no conjugada en el torrente sanguíneo, le pone un cinturón de seguridad, la sujeta firmemente y la lleva al hígado. Cualquier bilirrubina libre, o no unida a la albúmina, puede atravesar la barrera hematoencefálica.

Un alto nivel de bilirrubina en el torrente sanguíneo puede sobrepasar la cantidad de albúmina disponible, flotar en forma libre y volverse bastante peligroso. Una vez más, demasiada bilirrubina entrando en el cerebro puede causar kernícterus.

Se puede ver el color amarillo en el corte de cerebro de abajo – la bilirrubina ha cruzado la barrera hematoencefálica y ahora se aloja en el cerebro. Esto es lo que estamos tratando de evitar.

Volvamos al UBER. La bilirrubina unida a la albúmina ha llegado al hígado, donde ocurren tres cosas.

La bilirrubina es absorbida por el hígado.

Dentro de las células del hígado (hepatocitos), la bilirrubina se conjuga.

Bilirrubina + ácido glucurónico (glucuroniltransferasa) = bilirrubina conjugada. Mediante un análisis de sangre, en el laboratorio se mide como bilirrubina "directa". La bilirrubina conjugada es soluble en agua. No puede atravesar la barrera hematoencefálica.

La bilirrubina conjugada se excreta en el intestino y, en el mejor de los casos, se expulsa.

En el intestino, la bilirrubina viaja hasta el íleon y luego al colon, esperando ser desmayada. Las bacterias en el intestino pueden convertirlo en estercobilina (que es lo que hace que las heces se pongan marrones) y urobilinógeno que regresa al cuerpo y se elimina (haciendo que la orina se vuelva amarilla).

Pero aquí está el truco.

Si permanece allí el tiempo suficiente, las bacterias intestinales pueden convertir la bilirrubina conjugada en bilirrubina no conjugada. Si la bilirrubina no conjugada permanece y permanece en el intestino, es absorbida de regreso al hígado a través de la circulación enterohepática. Y aquí vamos de nuevo

¡Por eso nos encantan las heces! Defecar ayuda a eliminar el pigmento de bilirrubina. (Hecho: el meconio es el color oscuro que se debe al pigmento de bilirrubina).

Ahora debería quedar claro por qué la bilirrubina en el torrente sanguíneo puede presentarse en dos formas:

No conjugado (indirecto) y

Conjugado (directo)

En el hospital puedo solicitar una prueba de bilirrubina sérica total (TSB). Se compone de las formas indirecta (no conjugada) + directa (conjugada) de bilirrubina. También puedo pedir bilirrubina directa sola.

Si la TsB (bilirrubina sérica total) es 14 y la bilirrubina directa es 0,5, entonces la bilirrubina indirecta es 13,5. Espero que eso tenga sentido.

La ictericia fisiológica

Hay que tener en cuenta dos tipos de bilirrubina alta en el bebé: fisiológica y no fisiológica.

La ictericia fisiológica es la ictericia que esperamos que se produzca.

La mayoría de los bebés se ponen un poco amarillos, ¿verdad? Se produce normalmente en el 60% de los recién nacidos a término y en el 80% de los prematuros

En los recién nacidos a término, el nivel máximo medio de bilirrubina es de 5-6 mg/dl. (Tanto tu nivel de bilirrubina como mi nivel de bilirrubina de hoy probablemente sean inferiores a 1 mg/dl).

La progresión de la ictericia (o el color amarillo) va de la cabeza a los pies

El pigmento de la bilirrubina puede verse en la piel, las mucosas y el blanco de los ojos.

Los recién nacidos tienen numerosos factores que son el motivo de la ictericia fisiológica.

Volumen sanguíneo elevado y aumento de la concentración de hematocrito (el hct infantil normal es 45-65)

Vida más corta de los glóbulos rojos fetales

La actividad del UDGPT neonatal es menor que la de los adultos.

La ausencia de la flora intestinal clostridial necesaria para la conversión de bilirrubina en estercobilina da como resultado una mayor concentración de bilirrubina en el tracto intestinal.

La enzima mucosa beta glucuronidasa es más activa en el intestino delgado del bebé. En el caso de una pared intestinal infantil más permeable, esta alta concentración de bilirrubina no conjugada produce un aumento de la circulación enterohepática.

En los bebés, un pequeño aumento de bilirrubina es algo normal, ya que el pigmento de bilirrubina actúa como antioxidante en las células, absorbiendo los radicales libres que podrían dañar las células.

SIN EMBARGO, un gran aumento en el nivel de bilirrubina puede ser peligroso.

La ictericia no fisiológica

La ictericia no fisiológica es una historia diferente. Puede deberse a:

Sobreproducción de bilirrubina oUna disminución del aclaramiento de bilirrubina.

Punto clave: la ictericia en las primeras 24 horas de vida NUNCA es normal y necesita una investigación inmediata.

Las causas de la sobreproducción incluyen:

Hemólisis: cuando los glóbulos rojos se desintegran. Una causa común de esto es la incompatibilidad ABO. Los grupos sanguíneos de la madre y del bebé difieren, lo que provoca una enfermedad hemolítica, es decir, una destrucción excesiva de los glóbulos rojos. Otra causa es la incompatibilidad Rh. Otra causa es la deficiencia de G6PD.moretones excesivos

Cefalohematoma. Se trata de una acumulación de sangre que normalmente se observa en uno o ambos lados de la cabeza en el área parietal. Se diferencia del caput succedaneum en que un cefalohematoma no cruza las líneas de sutura.

Una causa común de disminución del aclaramiento es que el bebé no defeque. Esto puede deberse a una mala alimentación.

Desplácese hacia arriba hasta la traducción al inglés y mire las imágenes #3. Taburete de meconio, #4. Cefalohematoma y #5. Un pequeño con ictericia. Esta publicación superó el límite permitido por lo que las imágenes no se pudieron publicar dos veces.

La próxima publicación comparará la ictericia por mala lactancia y la ictericia por leche materna.

Referencias

Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession, 7th edition. Mosby, an imprint of Elsevier Inc. 2011

Core Curriculum for Interdisciplinary Lactation Care. Edited by Suzanne Hetzel Campbell, Judith Lauwers, Rebecca Mannel, and Becky Spencer. LEAARC (Lactation Education Accreditation and Approval Review Committee). Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2019

Wambach K, Spence B. Breastfeeding and Human Lactation, 6th edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2021